[Full article available for view online at the OFFRAMP Journal Website]

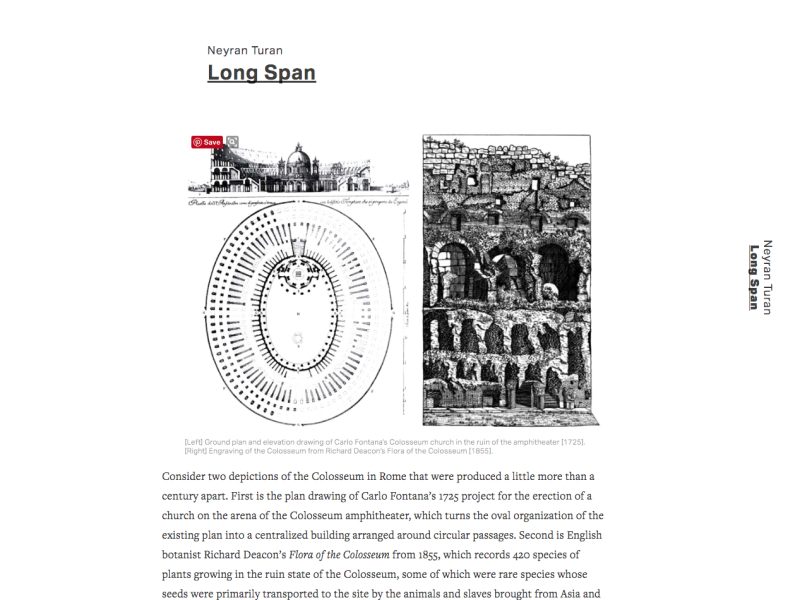

Consider two depictions of the Colosseum in Rome that were produced a little more than a century apart. First is the plan drawing of Carlo Fontana’s 1725 project for the erection of a church on the arena of the Colosseum amphitheater, which turns the oval organization of the existing plan into a centralized building arranged around circular passages. Second is English botanist Richard Deacon’s Flora of the Colosseum from 1855, which records 420 species of plants growing in the ruin state of the Colosseum, some of which were rare species whose seeds were primarily transported to the site by the animals and slaves brought from Asia and Africa for the city’s numerous spectacles. When positioned next to one another, these two depictions of the Colosseum put forward an important coupling of two different dimensions of architectural longevity. First, as illustrated by the Fontana plan, is the expanded life-span of a particular building after its original use and its inherent capacity for flexibility despite programmatic obsolescence. Second is the idea of material long-span, which complicates the delicate relationship between natural and man-made systems within an elongated temporality as presented by Deacon’s plant inventory.

Given our contemporary environmental, political and economic instabilities, a discussion on the architectural long-span might seem to point towards already exhausted undertakings in our field: foregoing the architectural object altogether for the sake of ultimate flexibility and ephemerality, foregrounding the idea of performance for a “realist” mission, or declaring the sole permanence of the architectural object with a relative suspension from questions of temporality. If we have already come to realize the dead-end quality of these discussions and their derivatives, then another question follows: What if our objects, geographies, and geologies cannot be neatly categorized as flexible or ephemeral but instead are in dire need to be reimagined in their expanded temporal and spatial long-span, i.e. in their unfamiliar permanence?