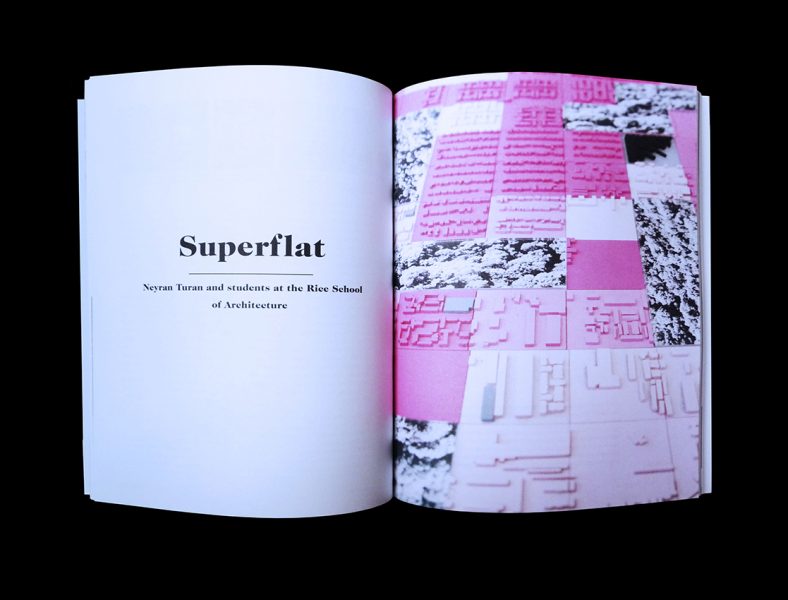

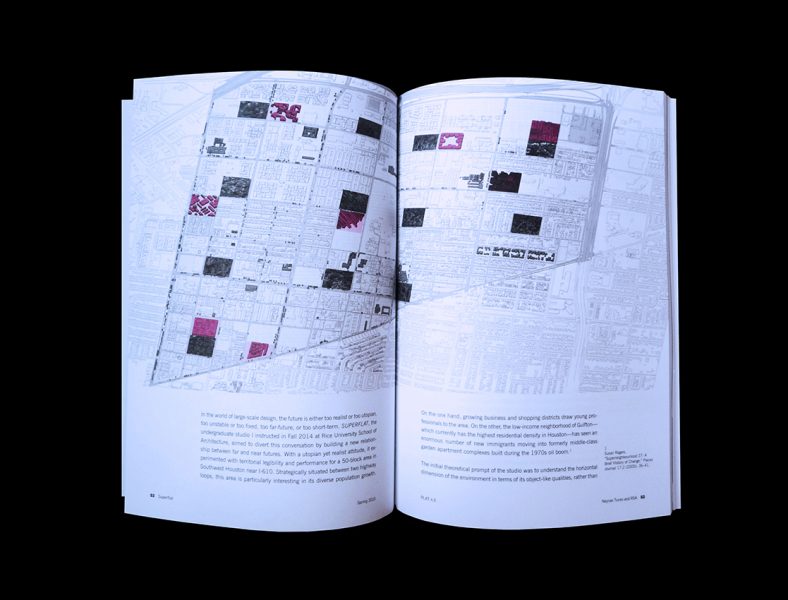

In the world of large-scale design, the future is either too realist or too utopian, too unstable or too fixed, or too far-future or too short-term. SUPERFLAT, the undergraduate studio I instructed in Fall 2014 at Rice University School of Architecture, aimed to divert this conversation by building a new relationship between far and near futures. With a utopian yet realist attitude, it experimented with territorial legibility and performance for a 50-block area in Southwest Houston near I-610.

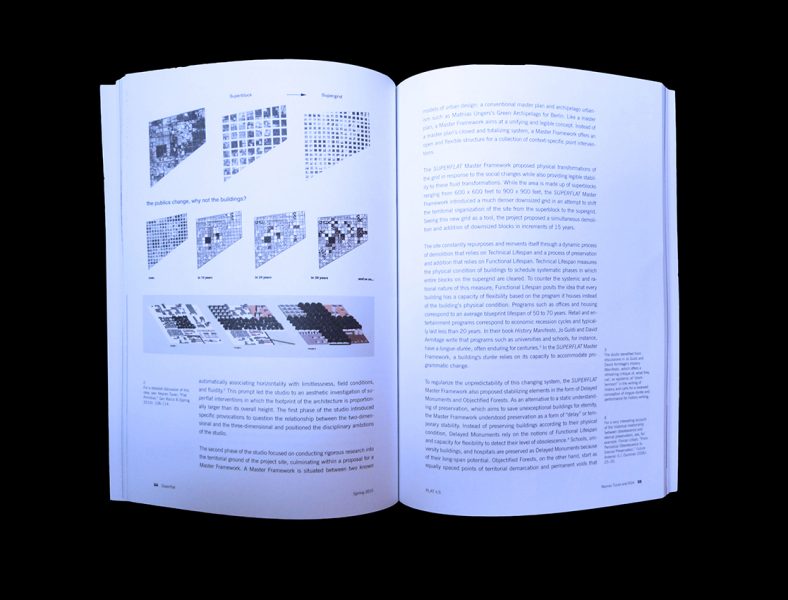

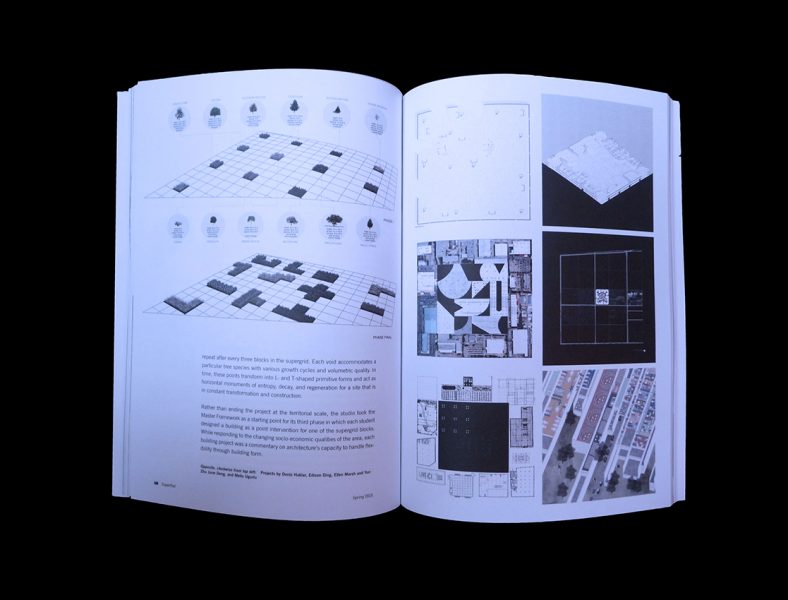

The SUPERFLAT Master Framework proposed physical transformation in response to the social changes while also providing legible stability to these fluid transformations. While the area is made up of superblocks ranging from 600 x600 feet to 900 x 900 feet, the SUPERFLAT Master Framework introduced a much denser downsized grid in an attempt to shift the territorial organization of the site from the superblock to the supergrid. Seeing this new grid as a tool for working within the increments of 15 years, the SUPERFLAT Master Framework project proposed a simultaneous demolition and addition of downsized blocks embedded in this supergrid.

According to the SUPERFLAT Master Framework, the site constantly repurposes and reinvents itself through a dynamic process of demolition that relies on "technical lifespan" and a process of preservation and addition that rely on "functional lifespan." To regularize the unpredictability of this changing system, the SUPERFLAT Master Framework also proposed a set of stabilities in the form of Delayed Monuments and Objectified Forests. As an alternative to a static understanding of preservation, which aims for saving unexceptional buildings for eternity, the SUPERFLAT Master Framework understood preservation as a form of "delay" or temporary stability.1 Objectified Forests, on the other hand, start as equally spaced points of territorial demarcation that repeat after every three blocks in the supergrid and, in time, transform into permanent voids, each of which accommodating a particular tree species with various growth cycles and volumetric quality. By transforming from points into L- and T-shaped primitive forms, these voids act as horizontal monuments of entropy, decay, and regeneration for a site that is in constant transformation and construction.

1 For a very interesting account of the historical relationship between obsolescence and eternal preservation, see, for example: Florian Urban, "From Periodical Obsolescence to Eternal Preservation," Future Anterior 3:1 (Summer 2006): 25–35.